Twenty-one years on, the legacy of the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 still reverberate. This year’s anniversary offers an opportunity to reflect on the unfortunate legacy in the proliferation of anti-terrorism laws. These laws have been used by numerous states, including many in Africa, to target dissent and limit the freedoms of expression, assembly and association. Between 2001 and 2018, African states were among over 140 countries worldwide that passed such counter-terrorism laws and other security-related legislation.

While the global counter-terrorism framework is clear about the fact that any strategy to combat terrorism must be based on respect for the rule of law , many countries in Africa, including those without a history of terrorist threats, now use anti-terrorism and related ‘security’ laws to silence critics. Eswatini is among the worst offenders.

Just a few months ago, the Kingdom of Eswatini, a nation subject to no threats from terrorism, used its Supression of Terrorism Act (STA) to target people raising legitimate concerns over actions of the government, which remains under absolute monarchical control. This time the target was journalist Zweli Martin Dlamini and his Swaziland News outlet. Backed by Eswatini’s Attorney General who designated Zweli as a ‘threat to national security,’ Prime Minister Cleopas Dlamini officially declared the journalist and the paper as entities that ‘knowingly facilitate’ the commission of terrorist acts.

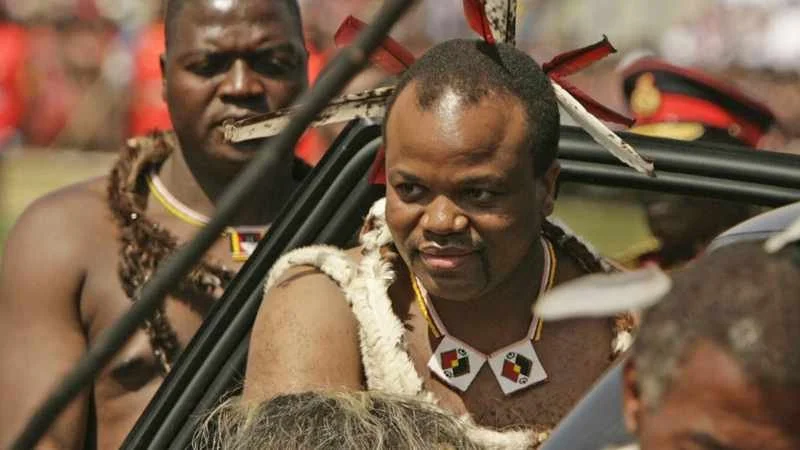

Zweli Martin Dlamini’s story mirrors those of several journalists and human rights defenders who report on the actions of King Mswati III and the government of Eswatini. He was forced to flee the kingdom for South Africa in February 2020 after being arbitrarily arrested and interrogated on suspicion of sedition after publishing two articles that were critical of Mswati and the monarchy.

With a severely limited number of independent news outlets in Eswatini, the Swaziland News website is a major source of independent news. The Eswatini authorities have even approached South African courts with a request to interdict Swaziland News and force it to send drafts of any article about the King, the government or the royal family for vetting before they are published.

The case of Zweli Dlamini is eerily similar to that of other human rights defenders, activists and journalists in many African countries – such as Algeria, Burundi and Cameroon, for example – those who have been arrested and charged using security-related legislation since the 11 September attacks.

The context in which human rights defenders are charged using security-related laws is similar across the continent. Usually this happens when there are pro-democracy protests and calls for democratic reforms – including during election campaigns, when there are unconstitutional changes of government, or when activists are critical of state actions. Authorities know that when the rationale of security and anti-terrorism is activated, constitutional protections are thereby lowered. Authorities are also aware that invoking security-related laws elicits sympathy and collaboration from other states.

In Eswatini, the STA was promulgated partly as a response to growing calls from political groups to be formally recognised and allowed to duly register and participate fully in political activities, including elections. The law was immediately used by royal authorities to designate the main opposition party, the People’s United Democratic Movement (PUDEMO) and three other organisations, as ‘terrorist groups.’

In July 2021, pro-democracy activists Mduduzi Bacede Mabuza and Mthandeni Dube were arrested and charged under the STA as pro-democracy protests spread across the country. As it stands today, they have now been in custody for over one year.

In Eswatini, the STA has been routinely used to target civic organisations, journalists and activists for offences such as wearing t-shirts bearing the logos of political groups or shouting slogans and making speeches at public gatherings - harmless acts of free speech that in no way constitute terrorism.

Civil society organisations in Africa continue to raise concerns over the weaponization and misuse of anti-terrorism laws, including in countries that genuinely face attacks from extremist groups. In Cameroon, for example, peaceful human rights defenders and journalists have been charged under anti-terrorism laws. In multiple countries of the Sahel and in Mozambique, the response to terrorism threats has been excessive, and in several instances targeted communities that are also victims of actual terrorist attacks.

Importantly, these heavy-handed responses by African governments are at complete odds with the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) principles and guidelines. The guidelines clearly outline that states should not use terrorism as a pretext to restrict fundamental freedoms.

Evidence from the last two decades shows that restrictions targeting journalists and activists do nothing to counter threats posed by real terrorist groups. Placing human rights defenders and journalists in the same category as terrorists who use violence and attack communities undermines the fight against terrorism in Africa, and worldwide.

Instead of targeting its citizens with security laws, the Kingdom of Eswatini in particular should instead embrace longstanding calls for democratic reforms as well as respect the rule of law and democratic institutions.

Put simply, it is long past time for authorities in Eswatini to stop using its Suppression of Terrorism Act – a complete misnomer if ever there was one – in its cynical attempt to hold back the peaceful tide for democratic change.

Kgalalelo Gaebee is a communications officer at CIVICUS and a passionate advocate of human rights and social justice

David Kode is advocacy and campaigns lead for CIVICUS who writes on constitutional issues, African elections, human rights, and defending civic space

DISCLAIMER: The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Vanguard Africa, the Vanguard Africa Foundation, or its staff.